Comparisons and Reflections on the Nantucket Community and Coastal Ecologies

By Alex Renaud

I have always had an affinity to the ocean throughout my life. Much of my childhood summers were spent making drip castles in the sand, swimming in the chilly New England waters, and walking along the sand with family and friends. I was most fascinated with the unique patterns that ocean waters would leave behind in the sand after flowing onto the beach. For me, our coastal environments have been places of belonging, learning and connection: yet also challenges.

The premier challenge I observed is the balance of desire for activity and ecological preservation. Beaches are closed for bird nesting seasons, or have severely limited access due to dune protection or sand nourishment. From my experience growing up in a coastal community in the North Shore of Massachusetts, I learned of the importance of this balance in the relationship between coastal environment and society, and became curious about how this relationship will need to change over time to accommodate the dynamic forces of the environment.

More recently, the challenge of access in our coastal environments became very apparent to me. Growing up, I was ignorant of the great privilege that I had to be able to head off to the beach on a moment’s notice. Beaches all around are often costly to park at and are inaccessible via public transportation. Beyond that, the remaining coastline is nearly completely commandeered by private developments. Even having the time to be able to enjoy these coastal environments is a privilege that I was not privy to until recently.

Coupled with this privilege of access to our coastal environments is education. I take pride in protecting familiar environments that I know are threatened by human activity. Yet this level of environmental stewardship is built upon education. I have elected to pursue a career in designing infrastructure for protecting this relationship between society and the environment because of my understanding of its value.

Through my two visits to the island this year, it is clear to me that Nantucket is grounded in its relationship with its local ecologies. There is immense support from the community to preserve beaches and marshes and cranberry bogs, but often the processes for this preservation are highly contested.

As part of the Envision Resilience Public Exhibition in early June, I heard many opposing viewpoints from my conversations with locals. Similar to my childhood town, pressures of increased privatization were the center of perspectives, positive and negative.

Further, in my second visit in late October, I became aware of the political landscape around Nantucket’s coastal landscapes. The island seems to have a very interconnected social fabric that can be a strength or major roadblock depending on the situation. Similar to the dynamics in my small town, each large decision becomes the buzz of the town and individuals perhaps feel more responsibility to have a firm perspective and to voice that to their community.

All of these conversations circle back to what kind of relationship the island community will have with its coastal ecologies. This balance that I discussed earlier crosses numerous industries and disciplines and involves every member of this island. Many desire to prioritize the protection of beaches, yet are much less concerned with the state of the coastal wetlands, such as on Brant Point, where they have been constrained over the years to slivers in numerous locations despite their great ecological value.

These priorities for protection were the most compelling windows into the Nantucket community that I experienced while visiting the island, and mirror the perspectives of those in my hometown community.

“It is the exchange of oral histories that will maintain cultural connectedness, guide societal values, and ultimately unlock the Nantucket community’s potential for the social resilience needed to power essential change. ”

The opportunity to interview a Nantucket resident was another window into the island community. Sara Jensen Carr, the professor leading the Northeastern University team for this challenge, introduced us to the concept of a photovoice interview. Commonly a public health practice, this style of interview allows the interviewee to structure this communication by sharing a series of photos taken that depict daily livelihoods.

My interview with a local islander, Guido Munoz, opened my eyes to more of the forces at play on Nantucket. I learned about the multi-generational stilt house in Madaket that fell victim to dynamic sedimentation and tidal forces, and the family that was left with minimal relocation options by the town after the efforts of their ancestors to secure and own this land washed away.

I also became aware of the great lengths that residents will go to maintain landscaping, despite unfavorable planting conditions and high costs–springing from social expectations for manicured lawns and non-native pastoral landscapes.

I even got a taste for the development pressures on the island that are diminishing the feelings of belonging, authenticity and comfort that are associated with the local character of Nantucket culture.

This experience ended up being integral towards how I framed my final design and communicated those ideas to the Nantucket community. By having a window into the livelihood of someone living in Nantucket, I was able to better understand how designed solutions to embrace rising sea levels could best fit this island community, not just any group of people situated along a coast.

It is the exchange of oral histories that will maintain cultural connectedness, guide societal values, and ultimately unlock the Nantucket community’s potential for the social resilience needed to power essential change.

It is this exact conclusion that should be the foundation for all forward-looking projects in coastal resilience. Every individual within a coastal community is or will be affected by the impacts of a changing climate on storm tides, local biodiversity, sediment transport and sea level rise. Therefore, every person has a valuable perspective that should be centralized in the solution designed for it to be truly resilient.

I quickly learned of this importance while interacting with locals at the exhibition of Envision Resilience back in June. Frequent questions spanned from, “is this my house?” or “You can’t develop here because of this upcoming project”, to “what happens if I don’t forfeit my land?” or “who will pay for this?”.

These interactions allowed me to think more critically about how my ideas and the communication of them addressed the following question: How does a resident interact with, create or support designed solutions?

This question uncovered other key aspects of community change that I had not yet considered in my design proposal: education, partnerships, politics and civic action, to name a few.

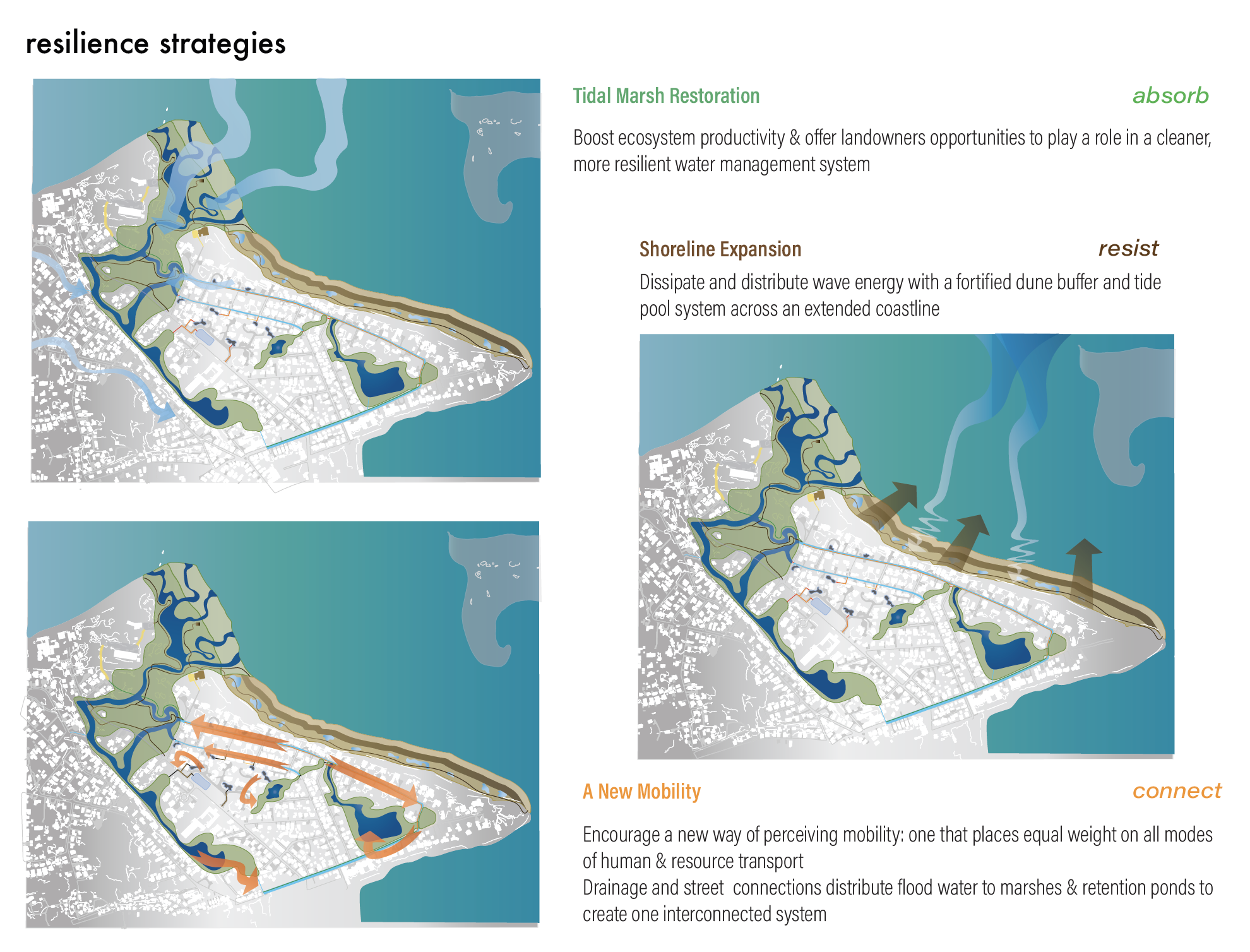

The mechanisms for community inclusion that I did include in my proposal highlight how residents need to be thoroughly engaged for Nantucket to endure the rapid changes occurring in its near future.

I introduced a simple tripartite funding mechanism for resilience-based retrofits of buildings and landscapes that would involve a homeowner or business owner, a third-party (either a local bank or foundation) and the municipality. This financial agreement would provide the retrofitter with capital to invest in needed infrastructure, and allow the third-party lender to receive payment back via the town through a special property tax, valued savings, or other means.

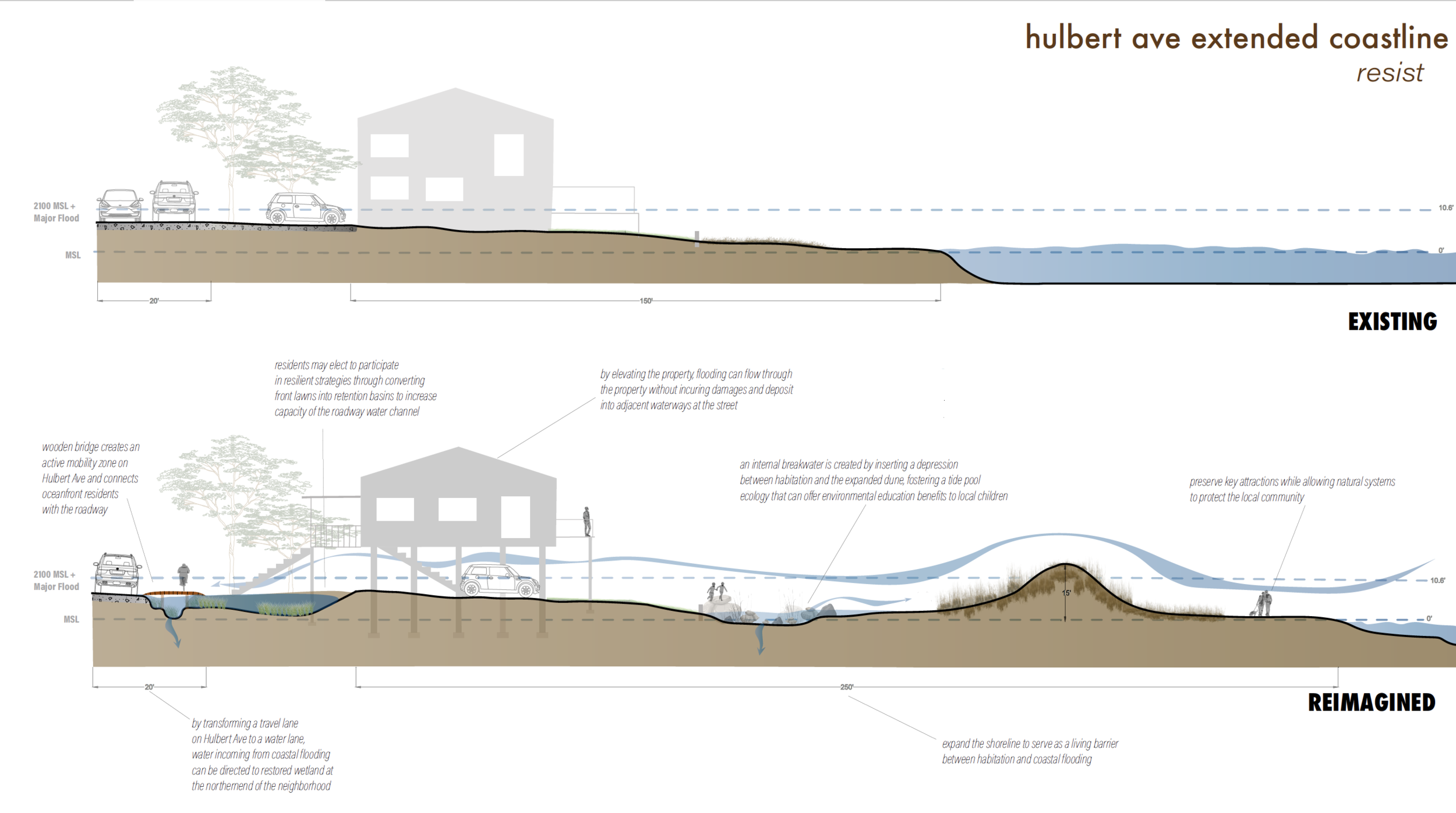

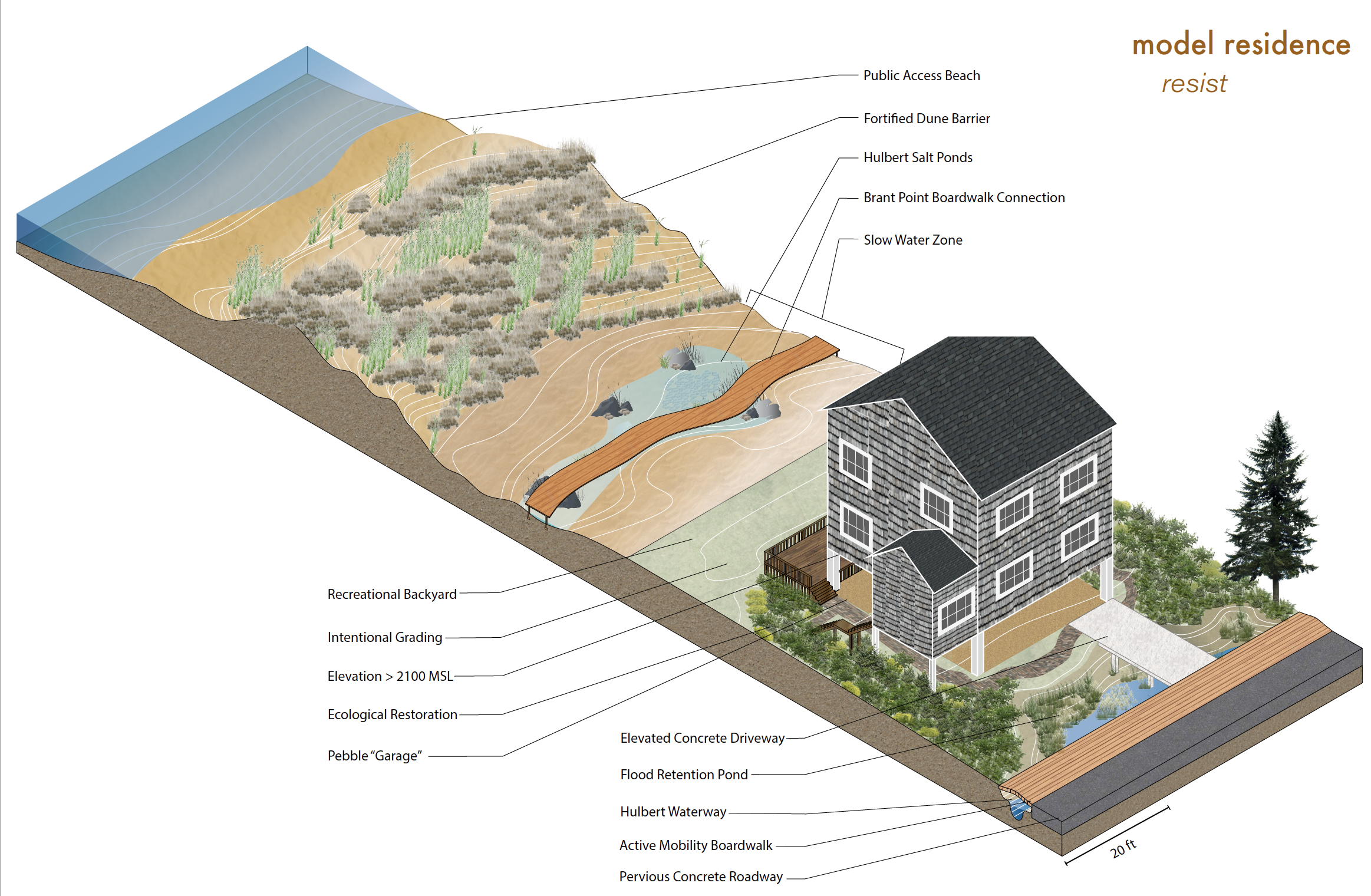

Further, I imagined how a resident can contribute to community-wide efforts. This contribution could take numerous forms. In one rendering, I depicted a resident elevating their home to guide stormwater flow to drainage infrastructure, restoring native plantings in their yard to slow down the force of flooding, and even constructing a detention basin to serve as extra capacity for water retention to mitigate flood damage in the neighborhood.

These were just a few of many solutions that can be offered to residents to take action in learning to live with water in the face of rising sea levels. I imagined through my proposal a collective vision for resilient infrastructure led by the town that is supported by these individual contributions to produce an interconnected network of solutions.

And this is just one piece of the story. I am excited at the thought of residents and other stakeholders engaging with all of the design proposals of Envision Resilience in the public exhibit this Fall and formulating their own ideas that may be better suited to their specific properties, neighborhoods or environmental conditions.

For my piece of this story of resilience on Nantucket island, I can leave feeling welcomed into the Nantucket community for being able to share my research and design ideas for living with water, and grateful for the insightful conversations I had with the locals while visiting in June and October.

I give my greatest appreciation towards the Envision Resilience team at Remain Nantucket for their extensive and thorough planning and execution efforts to ensure that this design challenge was a meaningful experience for the design teams, advisors and the greater community. This challenge kick-started critical conversations surrounding development, vulnerability and resilience that are pivotal towards progressing towards actionable solutions via advocacy, innovation and decision-making that will transform this island community to be resilient to the numerous challenges it faces today and in the near future.

In my short time experiencing this island, it is evident that the Nantucket community is here to stay. The population will find ways to leverage its inter-connected social fabric to transform its infrastructure and livelihoods to embrace rising seas. It will require continual efforts to capitalize on momentum, come to planning consequences, secure funding and implement resilient solutions equitably across the island. And all of this starts with these very discussions happening this year and beyond.

So, how are you going to contribute to the conversation?

----

Alex is in his fourth year of studying Environmental Engineering and Landscape Architecture at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. He plans to pursue a career within human-centered design of interactive spaces that combat climate change, particularly sea level rise and depletion of natural resources. He enjoys supporting local artists in the Boston community and exploring New England landscapes on his bicycle.