Stories From Ashore: Lamentation Concerning Wilkes’ Garage

At Envision Resilience, we support the exploration of science-based, design-led adaptations and we seek to amplify the anecdotal accounts of climate change in our community. In this series, Stories from Ashore, we will share stories of local Nantucketers and their experience with climate change, introduce you to people in our community who are imagining a future with increased water on their properties and discuss pathways forward. What will be your response to climate change?

By Alfred Sanford

I began swimming and sailing in Nantucket Harbor before I can remember. Growing older, in the 1970s, I became aware of the harbor's sophisticated wharf system. I gradually realized that the wharves had been developed by the simple farmers of Sherbourne when, in 1700, they decided to improve the Great Harbor to accommodate ocean-going ships. Having built the wharves in the water, they proceeded to build the town as an extension of them on the land.

In my adult years, I have done a lot of cruising under sail along the shores of the North Atlantic and Mediterranean and stopped in many ports. I saw how, like Nantucket, most of the ports had been created, reclaimed, if you will, from the sea by ancient, classical and medieval peoples with far less wealth than ourselves.

As the millennium approached, and Nantucket grew as a resort, I realized that Nantucket Harbor although an extraordinarily good harbor—thanks to the Sherbourners and the 19th century jetties—had for the 21st century two problems:

1. We need more waterfront to dock and service the recreational fleet, and

2. The ferries are overwhelming the recreational uses of the protected waters.

So, following the example of our predecessors, I thought, let’s see what it would take to make some more waterfront and better accommodate the industrial-scale ferries. My first drawings date from the late the late 1990s and the beginnings of the essay 2002. Publicity around the Wilkes Square project showed the vulnerability of Nantucket Harbor and Town to contemporary ideas and styles. So encouraged by friends, I wrote up the new harbor idea to show that we do not have to destroy what is so wonderful about Nantucket to accommodate the future.

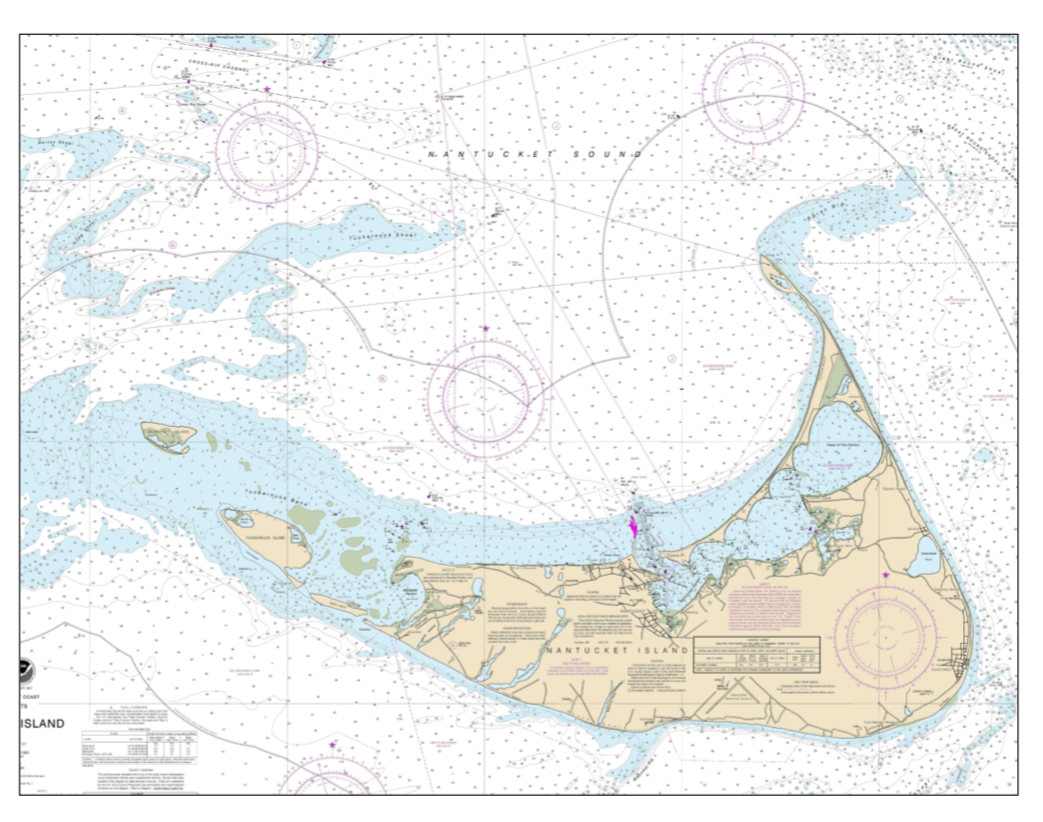

Figure 1. The essentials of a new port.

I have shared the essay with my friends as a conversation piece. Those who understand it love it. I have heard a little adverse criticism, but, as I heard it, it was based on misunderstanding. Mostly the essay has been ignored and I think few are aware of it.

Of the few who have seen it, the tunnel has scandalized some, who commingle it with the proverbial tunnel to the mainland. The delight of the project does not depend on the tunnel. I included it only to show a way to remove from the historic town truck traffic which may become destructive at some point in time if the Island grows much more intense; something I personally hope never happens.

I don't think the project is particularly sensitive to the water level changes. People have been using their shorelines in similar fashion all over the world for thousands of years. For example I have sailed by a coastline on Crete where a Roman galley harbor, 20 centuries old, is now 20 feet above the sea. It turns out that Crete (300 miles long) is slowly tilting. The west end is rising and the east end is sinking. Every hundred years or so (if wars have not intervened!) the coastal peoples have had to make adjustments to their improvements. So it is on Nantucket.

Lamentation Concerning Wilkes Garage OR A New Port for Nantucket (essay written by Alfred Sanford in 2016)

The essentials of a new port: Wilkes' garage:

I've never heard of Wilkes, but I am hearing about his garage. Twenty-five years or so ago the joke was going around that the first building in Nantucket to break the height limit would be a harbor-front parking garage. Today the joke is on us.

As 2016 comes to a close, the historic town of Nantucket finds itself squeezed between two powerful interests, one the continent of America, the other, 10 billion dollars worth of outside the-edge-of-town real estate. Historic Nantucket town finds itself separating those two powers, which do not wish to be separated. So the town finds itself confronted with an ongoing stream of projects, take down a house here, straighten out a curve there, move that institution out, bring this industrial scale scheme in. Each project lessens the town. At some point, the town will cease to be. We risk losing more than the historic artifact--we risk losing the Island's soul.

The old town of Nantucket is quaint, beautiful, comforting. It consists of streets that are for people, streets for people walking, people conversing, people shopping, people enjoying the companionship of their neighbors. Created in the 18th and 19th centuries, preserved by poverty for another century, Nantucket's streets were rediscovered in the 20th century by mainlanders who have taken such delight in them that the island has at least 10 times the value of the standard American design. This town, these streets, are why so many of us fell in love with the Island in the first place.

Wilkes, whoever he is, today, is asking us to industrialize the core of town by turning its heart into a transport hub. History be damned, streets be damned, we want to get there! Perhaps, he has forgotten the source of town's charm and the source of the Island's value. His plans abandon streets for people in favor of streets for BMW's and Stop-and-Shop 18 wheelers. He seems comfortable not only with hollowing out the core of town to make room for the traffic, but also happy to separate the town from its harbor with his new facilities.

Do not despair! Let’s take another look! Rather than transforming our streets for people into streets for machines, let's look at an alternative based on two ideas, what if we:

Move the necessary connection to America from the core of town out to its edge.

Utilize the plentiful water space around the island for the proper 21st century port that Nantucket needs.

In a word, rather than blighting 3 acres of downtown waterfront—the while not solving the transport problem—let's look at the feasibility of building a proper port on several hundred acres of land at the end of the West Jetty, land to be had for the cost of enclosing it with additional jetties. Such a port could fulfill many island needs while freeing downtown land for higher cultural, commercial and residential uses. Rather than a garage, a new port:

Imagine the existing Steamship Authority Wharf, the Straight Wharf Hyline facility, the Brant Point Coast Guard Station, plus the entire proposed Wilkes site relocated at the end of the West Jetty. Connect this new port with a road to town running down the West Jetty and connecting to Bathing Beach Road and North Beach Street.

Such a new port would benefit the town by:

Removal of about 50 daily ferry crossings of Nantucket inner harbor, making the harbor much more congenial to the water activities people come to Nantucket to enjoy.

Removal from the downtown of vehicular traffic associated with the ferry.

Allow Steamship Wharf and Straight Wharf and the Coast Guard Station to be repurposed for the cultural, residential and commercial interests of the town. Steamship Wharf might make a worthy replacement for the Town Dock.

Interestingly, the land value of Steamship wharf may well be more than the cost of building the new port.

The new port would benefit movement to and from the mainland by:

Reducing crossing times about 10%.

Providing sufficient staging area and parking for cars and trucks.

Remove small craft interference for the ferries as they land and depart Nantucket.

The new port would place the Coast Guard closer to their areas of rescue.

But this is just the beginning of what the new port could accomplish:

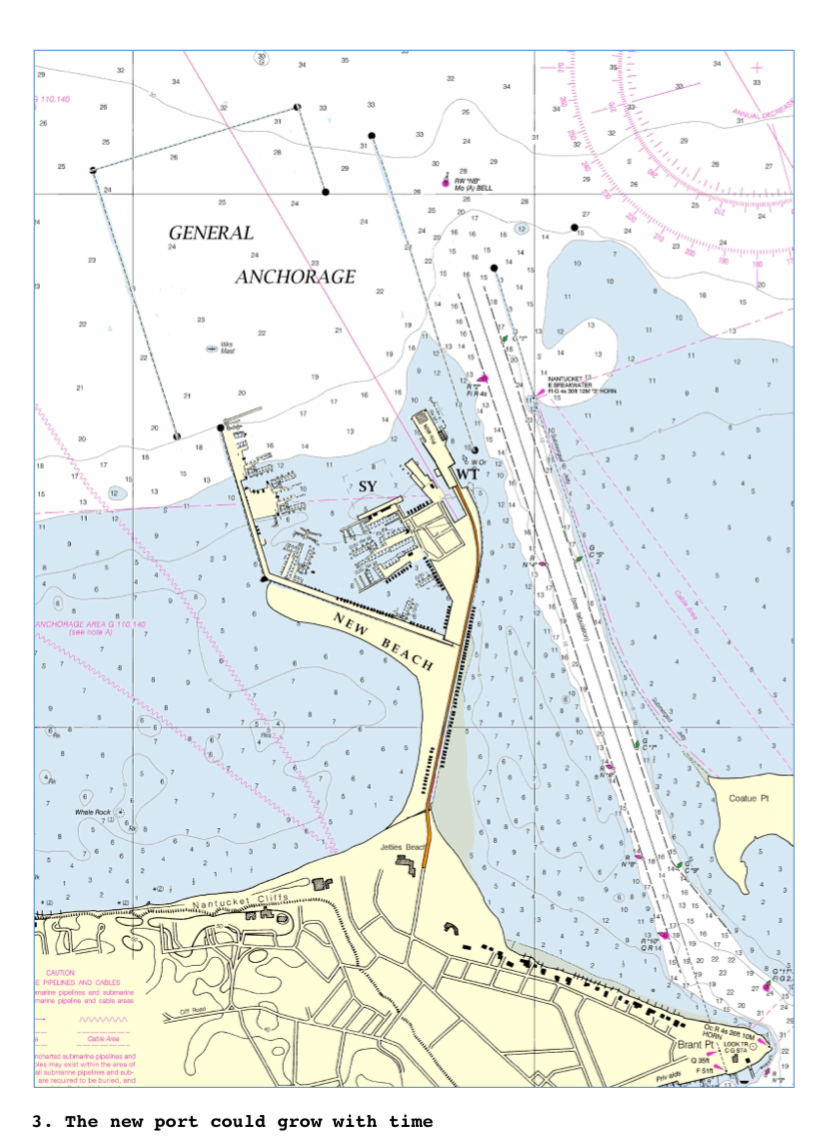

Nantucket needs a working waterfront. The Boat Basin is too small, and the mooring field has a long wait list. Nantucket's marine industry is scattered, unsatisfactorily, inland around the island. The new port could correct this at low cost and great benefit not only to the watermen, but also to summer residents, and to the hospitality industry catering to visiting yachtsmen. It will take time for the new port to develop and no planner can foretell exactly what will be needed or desired, but Figure 3 shows how the new port might accommodate:

General anchorage

Working waterfront, launch ramps, commercial fishing harbor boat repair yard

New boat slips

Super-yacht port

Enhanced Jetties bathing beach

Boathouses such as might improve the West Jetty.

Facilities not drawn for which there is room, are a commercial fish dock, boat ramps, a haul out lift and boat repair yard. In summer, a water taxi might operate from here to downtown. The new land shown in yellow west of the West Jetty and south of the new port is sand beach, a natural extension of Jetties beach. It would probably accrete naturally and could be augmented by dredge spoil from the new port.

Protection of the town:

The establishment of a new port would benefit Nantucket's historic town, her waterfront activities and the transport to and from the Island. But, by itself, it will not remove the heavy truck and vehicular traffic through the core of town.

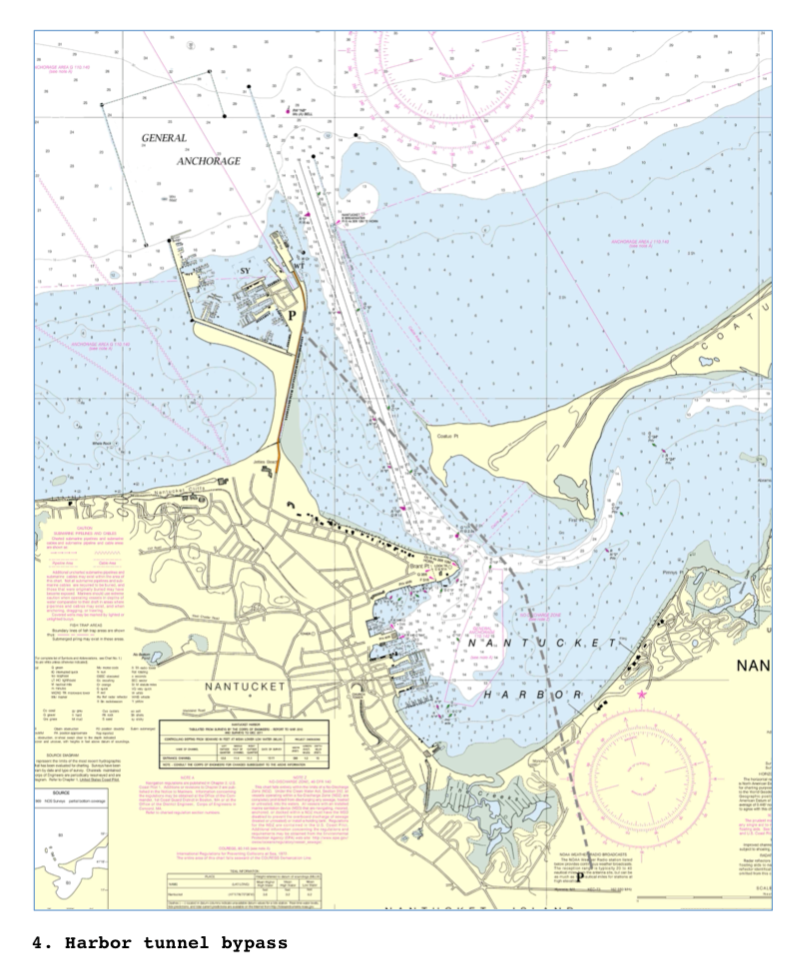

If we wish to preserve the streets of Nantucket for people, we need the heavy truck transport to bypass town as it serves the island. Figure 4 shows the 21st century solution to this 21st century problem: a tunnel under the harbor joining the new port with the Milestone Road near the rotary. The tunnel would be two miles long and easy to build in the sand of the harbor bottom.

The idea affronts at first, mostly because it is novel to Nantucket. But industrial scale transport, while new to Nantucket, is not a novel problem in itself. And the solution, a bypass, is a device used many times around the world to maintain valuable historic towns in an industrializing world. We can do it here in Nantucket.

Figure 5. Nantucket Harbor wharves as they were in 1831, 110 years after their original construction

The bypass would not only remove heavy trucks from center of town, it would allow car traffic from the east and south of the Island direct access to the new port and all its facilities without forcing that traffic through the core of town.

The past and the future:

Three hundred years ago, about 1715, the inhabitants of Nantucket were in crisis. Their existing harbor at Capaum Pond had become inadequate for their growing fishing industry. It was too small and shallow for the ships required by their new offshore ventures. They responded with the bold decision to develop a new port in what was then called the Great Harbor.

They began with the construction of five wharves, a huge undertaking for such a small group. Extending the wharves back onto land, they developed an entirely new town supplanting their existing village of Sherbourne. Within 30 years they had captured the European and North American lighting market and established Nantucket as a principal city of the world.

Today we have a similar crisis—and opportunity. Our town and harbor are overwhelmed by the industrial demands of mass tourism and summer resorting. The harbor is inadequate for both recreational use and the new transit traffic. The streets of town are inadequate for the necessary trucks and clogged with cars. Land for working waterfront is unavailable at any price. A new, new port could change this, removing large-scale shipping from the harbor and mainland traffic from town. So freed, the town could continue its role as the cultural, commercial and residential core of the island—maybe for a few hundred more years.

A beautiful future lies ahead. Shall we seize it?

— — —

Alfred Sanford has been involved with building and city design and spent 40 years working with the Old North Wharf in downtown Nantucket, as an owner and manager, proposing a restoration for it and rebuilding after the “No Name” storm in 1991.

Born in 1942 in Tennessee, Alfie spent summers in Nantucket where his passion for sailing manifested itself. His father taught me about the sea and sailing aboard his boats. After mathematics at Harvard, he graduated first in class at the Architectural School. In 1977, Alfie and his brother Edward began America’s first boat shop doing cold-molding on a production basis. At Sanford Boat, between 1978 and 1982, they produced 21 Alerion Class Sloops and oversaw the construction of eight more in later years.

Alfie has sailed many miles, aboard 29 different boats, usually as skipper or navigator, around the edges of the Atlantic and across it, from the Bahamas to the Norwegian Sea to the Aegean, including 14 voyages to Bermuda (7 racing), eight round trips from Nantucket to the Bahamas, four to the Maritimes and four trans-Atlantic passages, three in IMPALA, my lovely 57-foot S&S yawl. Wooden Boats for Blue Water Sailors is my second book. I wrote the pilot for Nantucket waters, Sailing around Nantucket, in 2015.