Strengthening Climate Resiliency with Indigenous Lessons and Values: A conversation with Anjelica S. Gallegos

New England Foodways Reconnecting Nantucket with Traditional Cultures of Water, Land and Food by Yale team students Anjelica Gallegos, Daoru Wang and Robin YangThe 2021 and 2022 Envision Resilience Challenge studios have focused on Nantucket and Narragansett Bay, traditional territory of the Wampanoag, Narragansett, Pokanoket and Niantic First Nations. We acknowledge all those who have ancestral rights to the lands of Nantucket and Narragansett Bay—who in their wisdom have sustained generations of people and culture through a balanced relationship with nature and a close tending of the land and water. We move forward with this ethic of stewardship as the framework for all of the work carried out.

“Land acknowledgements highlight the ongoing stewardship by Indigenous peoples, uplift Indigenous voices, and allow everyone to consider how to advance and contribute toward the connected communities we live in…acknowledging the unique and enduring relationships that exist between Indigenous peoples and their traditional territories of lands and waters is a vital first step towards reconciliation, support, and growth.”

By Jolie Jaycobs

In 2021, Anjelica S. Gallegos—along with three peers in her Masters program at the Yale School of Architecture—took part in ReMain Nantucket’s inaugural Envision Resilience Challenge. Anjelica’s project examined the ways Nantucket Island can better utilize its shorelines to focus on adaptation, ecosystem balances and the regional food network. Her team proposed a new circular economy centered around aquaculture in Brant Point, a low-lying and flood-prone neighborhood on the Island. The team’s ideas for regenerating community connection with the land, eating from local sources, and evolving balanced maritime living, stemmed from the Island's rich history of resilience and connectedness by Indigenous peoples and maritime quakers.

Anjelica S. Gallegos, Designer, Page Southerland PageNantucket’s Indigenous inhabitants lived in accordance with the life cycles of estuaries, animals, plants and weather patterns. The ecological knowledge and collective consciousness that precipitated from this lifestyle was reflected in communal spaces, mobile dwellings, and shared resource values, which Anjelica’s team worked hard to incorporate into their proposal. Looking back to the whaling age, the team also recognized Nantucket as a small but long standing beacon to the rest of the world, centered on innovation and economic leadership.

“Today, Nantucket has [another] opportunity to become a leader in sustainable living, celebrating its history of collective thinking and connection to the ocean by existing reciprocally with the sea in the way we live, grow and eat,” said Anjelica. Those earlier island habitants prove “the spirit of Nantucket has been to embrace challenges and recognize potential.”

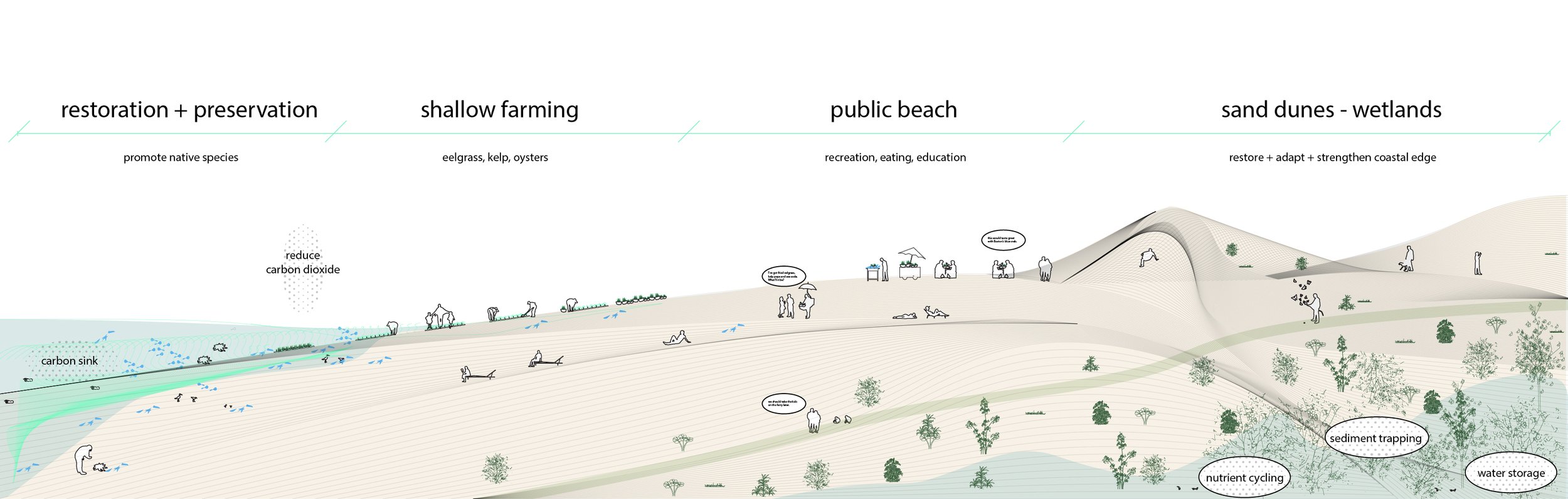

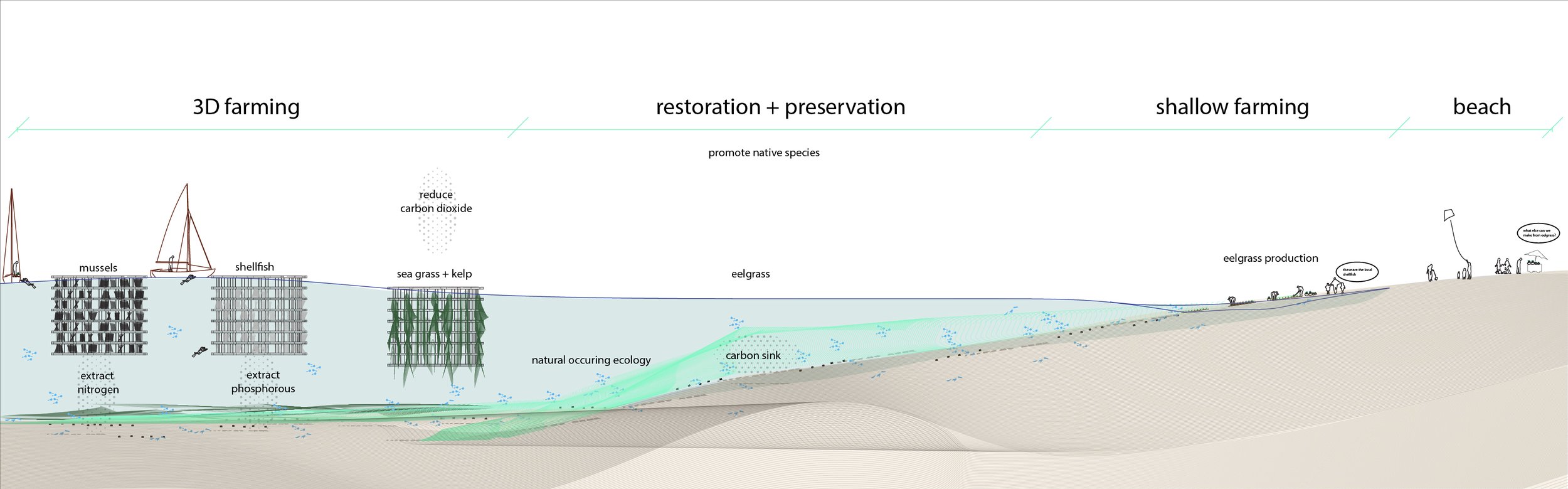

To reflect these values in their Envision Resilience project, Anjelica and fellow teammates Daoru Wang and Robin Yang, explored dynamic landforms to mitigate sea level rise. These landforms extended the beach, introduced sand dunes and restored eelgrass beds. Moreover, these extended spaces served as places for people to cultivate their own aqua-gardens and learn from one another.

“Responding to sea level rise, flooding and coastal erosion, we used modes of regeneration, mitigation and migration to focus on incremental adaptation” she explained. Some of her team's designs are included below.

New England Foodways Reconnecting Nantucket with Traditional Cultures of Water, Land and Food - Anjelica Gallegos, Daoru Wang, Robin Yang

Reflecting on her time as a student in the program, Anjelica shared a deep appreciation for “The structure of the studio and the unequivocal resources available for students to draw from...Being around so many practicing and academic professionals across disciplines from architecture to environmental science was an eye-opening experience. It truly fit with the core of Envision Resilience’s message: multiple perspectives and knowledge bases are needed to create solutions for the future.”

Having now completed her degree, Anjelica works at Page Southerland Page as an architectural designer in New Mexico and serves as Director of the Indigenous Society of Architecture, Planning, and Design (ISAPD).

“The core of Envision Resilience’s message: multiple perspectives and knowledge bases are needed to create solutions for the future.”

In 2018, Anjelica co-created the first chapter of ISAPD with two Indigenous colleagues, Summer Sutton and Charelle Brown, while studying together at Yale. ISAPD focuses on increasing international knowledge, consciousness, and appreciation of Indigenous architecture, planning, and design in both academia and the professional realm.

“ISAPD works toward fundamentally supporting and increasing the representation of American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, First Nations, Aboriginal Australians, Māori, and other Indigenous Peoples in these fields,” Anjelica explained. “We focus on encouraging Indigenous youth to consider joining the architecture, planning and design fields as solution makers and visionary leaders for their own communities.”

Anjelica’s work is invaluable in ensuring that Indigenous architectural knowledge gains recognition and gets upheld throughout the field.

“Recognizing the history of sites and recognizing that the land has a memory that started before the settler experience is foundational,” she said. “Land acquisition in the U.S. is tied to specific fulfilled and unfulfilled articles of agreement with Indigenous nations and from land cession of Indigenous territories. Academia has the opportunity to lead the way toward coupled tribal land acknowledgements by researching and stating their ties to these documents while actively creating opportunities for Indigenous peoples to benefit from.”

”Bringing the people who have this knowledge into projects, conferences, academia, or any opportunity for mutual exchange of ideas and information works toward preservation and innovation for all sides,” she said.

On the small island of Nantucket and across the Narragansett Bay region, we too have a role to play in recognizing and honoring the presence of our Wampanoag, Narragansett, Pokanoket and Niantic First Nations predecessors.

Anjelica shared the map below, which came out of her research on Indigenous living in the 17th and 18th centuries on Nantucket. She designed a series of similar maps, providing a unique time and space perspective on where Nantucket's Wampanoag peoples historic sites sit, and how the spaces between native islanders and maritime quakers converged on the island. These maps begin to depict spatial living boundaries, conditions, and mobility in connection to seasonal change and subsistence living.

Indigenous Living 17-18 Century Anjelica S Gallegos Nantucket Algonquian Studies Elizabeth A. LittleAnjelica also shared an indigenous story, which carries a lesson we can learn from. She told it like this:

The Wampanoag, the People of First Light, have lived along the southeastern coast of Massachusetts for time immemorial and have a story about the origin of the Appanaug - a word which means “seafood cooking”. At one point in the story the people fell out of touch with the land and other beings. They were forced to provide for themselves instead of depending on their Giant friend, Maushop, who also created Nantucket. They soon found when they worked for themselves, everything that they needed was there. One of those ways of survival that celebrates all that is around them— the plants, the animals and the water—is Appanaug.

The lessons that come from stories and perspectives like this exemplify the knowledge type ISAPD brings to the forefront of sustainable architecture. The precipitating insights will play a critical role in driving architecture, sustainable design and environmental resilience forward.

“The original communities of any land are the histories we build upon. Those communities had intergenerational knowledge of particular natural processes, further history of the site, and methods of adaptation that have been fine tuned over centuries,” said Anjelica.

Respecting and learning from that knowledge base we so literally build upon demonstrates why it is vital for designers and planners to reflect on the earliest inhabitants and their ways of life.

Climate scientists have started to collaborate with Indigenous communities in order to innovate climate change solutions that will revitalize and protect landscapes. Planners and architects must also work to explore the wealth of Indigenous knowledge sources from a millennia of ecological experience on this land. Anjelica pointed to indigenous thought principles such as “collective thinking, restraint, reciprocity, long-term sustainability, acknowledging the history of a place, and abiding to natural cycles” as tools that architectural design can incorporate. Utilizing these tools could manifest into appropriate material selection, improving the life-span of built works, implementing holistic construction methods, meaningful and accredited naming of spaces, and more.

In 2022, The Envision Resilience Nantucket Challenge was extremely fortunate to welcome Anjelica back for its second season, this time as a juror. After experiencing the challenge two years in a row, from two different perspectives, Anjelica emphasized how Envision Resilience embraces collaboration to build a space for creative and holistic ideas.

“It’s ’s vital for a range of people to collaborate on researching, creating, and building new models of living at multiple scales. These models of living can help shift society toward a standard where humans, non-humans, and the ever changing environment have positive meaningful exchange,” she said.

“What matters is staying true to your conviction, carving out opportunities, and staying in wonderment of the unknown possibilities.”

These processes were relevant on both sides of the challenge, and remain a cornerstone in Anjelica’s architectural mission today. Anjelica has carried the Challenge’s focus on collaboration, local engagement and sustainability into her work.

ISAPD collaborates with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous folks who have interest in Indigenous architecture. Anyone can become a member - “I think we need people everywhere, in different spaces, and with their own perspectives and bodies of knowledge to really create sustainable solutions and productive change.”

Anjelica shared hopes that, in order to expand the value of Indigenous collaboration and knowledge, Indigenous case studies and principles will be included in more core curriculum. She felt that the Yale School of Environment acts as a strong example of a program “incorporating the contemporary Indigenous knowledge keepers into curriculum, research studies, projects, and community.” Perhaps most importantly, “Including Indigenous scholars and communities in discussions and as teachers sparks new thoughts and challenges.”

In addition, The Yale Forests & Indigenous Narratives: A Working Syllabus is a resource that includes Indigenous knowledge in discussions of sustainability, land stewardship, and placemaking. This resource could be a great starting place for anyone interested in learning more about this work.

In conclusion, Anjelica looked with us to the future. Despite the harms and fears we must meet in the face of climate change, Anjelica feels reason to remain optimistic. That optimism stems from the belief that “people will shift toward becoming congruent with the natural world. With this appreciation alongside never before seen challenges, different knowledge bases will become more accepted and will stimulate a unique development of ideas. The right leadership and people in the field who create, allow, and carry out multiscale solutions for climate change will become the preservationists and builders of tomorrow.”

“Small ideas turn the tide,” she said. “Ideas and designs of all sizes are necessary for positive change. Sustainability and reacting to changing climate conditions is a way of thinking that can be carried throughout any studio or project. Striving for perfection can be a misuse of time and not everyone will see value in your work; what matters is staying true to your conviction, carving out opportunities, and staying in wonderment of the unknown possibilities.”

As coastal communities worldwide grapple with the concerns, challenges, and decisions around our changing climate, while aiming to envision thoughtful and resilient responses, this notion of small ideas turning the tide is an important one. While we might not all be architects who more literally play a role in designing the future, we all must contribute to shaping the world into what we want it to be. By including more voices and perspectives we can build a broader base of small ideas, small actions, and small dreams that can bind together and turn the tide for a better future.

Thank you to Anjelica for her time contributing to the Envision Resilience Challenge and for sharing her insights and story with us.

About the author: Jolie grew up on Nantucket Island. She graduated from Haverford College in 2020 with a B.A. in Environmental Studies. Since then she has worked for a few nonprofits in environmental advocacy and education. She now works in faculty support at the Harvard Business School. When she visits the island Jolie still loves to spend time exploring Nantucket’s beautiful natural places through biking, running and sailing.